| UML软件工程组织 | |||

| |

|||

|

|||

| from The Rational Edge: Accurate requirements are an essential part of the formula for software project success. This article explains why, and describes a three-fold approach to effective requirements documentation. A Fortune 100 company embarked on a project to design and build a sophisticated software package that it would ultimately deploy to its offices throughout the world. Two years and about $10 million later, the field offices refused to use the software because it didn't do what it was intended to do. Instead of helping to streamline an important business process, the software actually hindered it. In another case, a leading software integrator was awarded a contract by the procurement organization for a major utility company. Later, that organization was shocked when the integrator informed it that, based on"true" client requirements, the project's scope had increased twofold. Do these stories sound familiar? Why do things like this happen? According to a recent survey by the Standish Group1 of more than 352 companies reporting on more than 8,000 software projects:

The Standish Group survey also asked respondents to identify the causes of these failures. Table 1 shows the top three reasons why projects are "impaired." Table 1: Top three project impairment factors (Standish Group survey)

As this table shows, poor requirements are the biggest problem. If it isn't clear what you are supposed to build, how can you estimate the cost of building it? How can you create a project plan, assign resources, design system components, or create work orders? You need accurate requirements to perform these activities. Of course, requirements evolve as a project proceeds, but carefully worded basic requirements provide a starting point. Then, as the project progresses, you can fill in details and update planning documents as the requirements evolve. So what is a requirement? This article attempts to explain this commonly misunderstood term. Rather than supplying a definition up front, we will discover one by understanding first why we need requirements, and then examining the content of the different documents we use to capture them. Why do we need requirements? We use requirements for a variety of purposes, including:

Individuals throughout an organization have a vested interest in producing solid requirements. Whether you're a client or involved in procurement, finance and accounting, or IT, you are a major stakeholder in the requirements management process. Many project teams treat requirements as a statement

of purpose for the application and express them in very general

terms, such as: "The system should have the ability to create

problem tickets for outage notifications." But is this a solid

requirement?To answer this question, let's look at how we document

requirements. Classifying and documenting requirements Requirements are not requirements unless they are written down. In other words, neither hallway conversations nor "mental notes" constitute requirements. We typically capture requirements in three separate documents:

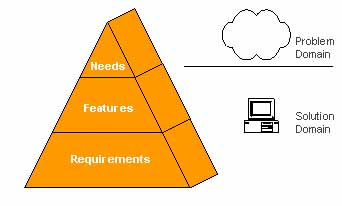

At my organization, we associate about a half dozen attributes (e.g., priority, status, etc.) with each requirement to help with decision making, scheduling, and so on. The information contained in one requirement document should be referenceable in the others. For example, the information recorded in the Software Features document should support and be traceable to one or more items listed in the Stakeholder Needs document. To better understand the relationships among these documents, let's return to my earlier question about whether the statement, "The system should be able to create problem tickets for outage notifications" is a valid requirement. The answer is, "Not yet." What this statement expresses is a need. Capturing this need is a step toward formulating a solid requirement, but the statement cannot stand alone; you must first translate it into one or more features that you capture in a Software Features document. Those features, in turn, must then be detailed in the Software Requirements Specification document. Using these three separate documents also helps to simplify the process of requirement reviews. Although an executive manager might be a reader/approver for the Stakeholder Needs and Software Features documents, he/she may delegate responsibility for reading and approving the more detailed Software Requirements Specification. Maintaining separation among these different documents allows specific readers to understand specific parts of the system. It also promotes better accountability -- a key element for a successful software development process. Documenting stakeholder needs Let's look at what each of these documents contains (see Figure 1). We'll start with the Stakeholder Needs document. As we describe what to capture in each document, keep in mind that whatever needs and requirements you formulate at the outset of your project will evolve as your project proceeds. If you are using an iterative development approach, you should assess your requirements after each iteration, and if you make changes in one document, you should update the others as well to maintain consistency.

Stakeholder needs, which are part of the problem domain, describe what stakeholders require for a successful project. In other words, needs describe what the application should do to help improve or lower the cost of a business process, increase revenue, or meet regulatory or other obligations. Documenting stakeholder needs involves identifying, understanding, and representing different viewpoints. Often, users and stakeholders don't know how to solve the entire problem but are experts at explaining what they need to do their job better. Each stakeholder sees the problem from a different perspective. Therefore, you must understand the needs of all stakeholders in order to understand the entire problem domain. The first step is to identify all stakeholders. Users represent a class of stakeholders, but by no means do they represent the interests of the whole organization. Other classes of stakeholders may come from finance and accounting, procurement, and IT, as well as from other departments or organizations that directly or indirectly support or benefit from the project. You should identify (and recruit) at least one representative from each stakeholder class who will speak for the entire class. Also, document your list of stakeholders so that everyone knows who is representing each class. You can elicit needs from stakeholders using various techniques, including one-on-one meetings, questionnaires, storyboarding, and Joint Application Development (JAD) sessions. Explanations of these specific techniques would be beyond the scope of this article, so for now, just be aware that how you ask questions and the format you use are important aspects of the process. Let's look at a hypothetical project aimed at streamlining a help desk application for a major corporation's IT department; we'll use this project as an example throughout the remainder of this article. Imagine that you, a project team member, have met with the help desk manager and formulated a requirement that says, "He needs to be able to increase the number of support calls his team can handle by 30 percent, without increasing headcount." Note that this need requirement provides little detail, but it clearly conveys what the client wants at a high level. Ambiguity is expected at this stage; you will capture more detail later. But not all the needs you gather will describe system functionality. For example, a stakeholder from procurement or finance might say, "The budget for the initial implementation of the application help desk project cannot exceed $350 thousand." Of course, this perfectly valid need might conflict with other stakeholders' needs that might cause the budget to exceed $350 thousand; resolving conflicting needs is a normal part of the requirements management process. However, in the beginning, you should focus on eliciting and recording the perspective of each stakeholder; conflict resolution can come later in the process. Documenting software features After you have defined stakeholder needs, you must translate them into a set of distinct system features. What's the difference between needs and features? Needs do not indicate a particular solution; they simply describe the business need. For example, if a stakeholder says, "We need to streamline the help desk's application support process because we can't keep up with the calls," that person is expressing a need that the development team can translate into a feature. However, if the stakeholder says, "We need a Web-enabled system so that customers can enter their own support requests," the stakeholder has already translated the need into a feature. It is perfectly fine for stakeholders to express themselves in any way they wish; often, you will want to ask additional questions to clearly understand both needs and features. I'll explain why in a moment. For now, let's define what a feature is. A feature is a service that the system provides

to fulfill one or more stakeholder needs. Let's return to our example of a help desk support application. Table 2 shows three stakeholder requests expressed as needs. Table 2: Stakeholder needs

Table 3: System features mapped to stakeholder needs

Documenting software requirements After you analyze and generalize needs and features, it's time to move deeper into the solution domain by analyzing and capturing the system requirements. Now we have enough understanding to define a requirement as: ...a software capability that must be met or possessed

by a system or a system component to satisfy a contract, standard,

or desired feature.

We can classify the requirements themselves into two categories: functional requirements and non-functional requirements. Functional requirements present a complete description of how the system will function from the user's perspective. They should allow both business stakeholders and technical people to walk through the system and see every aspect of how it should work -- before it is built. Non-functional requirements, in contrast, dictate properties and impose constraints on the project or system. They specify attributes of the system, rather than what the system will do. For example, a non-functional requirement might state: "The response time of the home page must not exceed five seconds." Here are some qualities that should characterize the descriptions in your Software Requirements Specification document:

To document functional requirements you must capture three categories of information:

Use cases define a step-by-step sequence of actions between the user and the system. Organizations are rapidly adopting use cases as a means to communicate requirements because they:

The end result of a use case is a complete requirement. In other words, when you communicate via uses cases, you don't leave it up to the developers to determine the application's external behavior. Specifying the format and details for creating a use case goes beyond the scope of this article, but it is important to capture use cases using a standard template that contains all the components of a complete specification. These include a use case diagram, primary and assisting actors, triggering events, use case descriptions, preconditions, post conditions, alternative flows, error and exception conditions, risks and issues, functional capabilities, and business rules. Note that use cases do not result in requirements until you define functional capabilities and any business rules that apply to the use case. Functional capabilities define what specific action the system should take in a given situation. You can relate functional capabilities directly to a specific use case or define them globally for the entire system. A functional capability for our example application might be, "When creating the support request, populate the "created by" field with the user's logon id." Business rules state the condition under which a use case is applicable and the rule to be applied. For instance, a business rule related to a use case might state, "Only the system administrator may modify the name of the customer in use case UC01." Like functional capabilities, business rules can be directly related to a use case or defined globally for the entire system. Capturing non-functional requirements Non-functional requirements are attributes that either the system or the environment must have. Such requirements are not always in the front of stakeholders' minds, and often you must make a special effort to draw them out. To make it easier to capture non-functional requirements, we organize them into five categories:

Usability describes the ease with which the system can be learned or used. A typical usability requirement might state:

Reliability describes the degree to which the system must work for users. Specifications for reliability typically refer to availability, mean time between failures, mean time to repair, accuracy, and maximum acceptable bugs. For example:

Performance specifications typically refer to response time, transaction throughput, and capacity. For example:

Supportability refers to the software's ability to be easily modified or maintained to accommodate typical usage or change scenarios. For instance, in our help desk example, how easy should it be to add new applications to the support framework? Here are some examples of supportability requirements:

Security refers to the ability to prevent and/or forbid access to the system by unauthorized parties. Some examples of security requirements are:

In a software development project, requirements drive almost every activity, task, and deliverable. By applying a few key skills and an iterative development approach, you can evolve requirements that will help ensure success for your project. Use separate documents to record needs, features, and requirements, and improve the accuracy of your requirements by sharing responsibility for review. With these documents you can also establish traceability between needs, features, and requirements to ensure that your Software Requirements Specification will continue to match up with business objectives. It is typically very costly to fix requirement errors that remain undiscovered until all the code has been written. Use cases can help you avoid such errors by communicating requirements to all project stakeholders; developing the system in iterations will help you identify what requirements you might need to specify in more detail or change. Remember: When gathering stakeholder input, ask about non-functional considerations as well as requests for specific functionality. And keep in mind that solid requirements are themselves the most important requirement for producing useful, high-quality software. |

组织简介 | 联系我们 | Copyright 2002 ® UML软件工程组织 京ICP备10020922号 京公海网安备110108001071号 |