from The Rational Edge: This article discusses

the concept of Agile Software Configuration Management,

a style of SCM geared toward agile development methods.

It also describes how the IBM Rational SCM toolset can

be implemented to support agile projects.

It wasn't that long ago that agile development methods

such as eXtreme Programming (XP), Dynamic Systems Development

Method (DSDM), or Scrum were introduced as new and somewhat

controversial methods for delivering software development

projects. Today, agile development practices such as

iterative development, test-driven development, and

continuous integration are commonplace and have been

accepted and absorbed as an alternative approach to

software development. Whatever your beliefs or experience,

you cannot deny that agile development projects can

and have proved successful in delivering functionality

on time and to budget.1

This article discusses a specific aspect of agile

development -- the concept of Agile Software Configuration

Management, or Agile SCM, a well-designed, light form

of SCM that can be used by software development projects

practicing agile development methods. As part of this

discussion, I will also look at how an enterprise SCM

toolset, such as the IBM Rational SCM toolset, can be

implemented to support agile projects.

The approach that most agile development methods share

is the direct involvement and interaction with users

or customers, and the development of functionality in

frequent, short iterations (typically two to twelve

weeks). Typically, at the start of each iteration, agile

teams negotiate with the customer to define new features

or change requests. These are estimated by the developers

and then subsequently prioritized by the customer for

the next iteration, as illustrated in Figure 1. A backlog

of any features or change requests that have not been

implemented in an iteration are kept and, together with

any new requests, are re-prioritized by the customer

for the next iteration. Developers are permitted to

work on requests for the current iteration or to carry

out re-factoring and simplification of existing code

as necessary. The intention behind this is to keep design

simple and prevent gratuitous feature bloat. Code is

also continuously integrated; it is implemented, tested,

and committed frequently in very small units, with an

automated build process being invoked at commit time

to check for integration errors.

Figure 1: At the start of each iteration, agile

teams negotiate with the customer to define new features

or change requests. These are estimated by the developers

and then subsequently prioritized by the customer for

the next iteration.

Like any software development process, agile development

methods require a core and supporting team-based environment,

something which has traditionally been called software

configuration management, or SCM. Unfortunately, some

practitioners regard SCM as an archaic and unnecessarily

controlling discipline. But this is a misconception.

While it is true that too much and the wrong kind of

SCM can strangle an agile development project, it is

also true that agile practices such as iterative development

and continuous integration simply couldn't function

without SCM.

So, just how much and what form of SCM do you need

for these types of projects? To answer these questions,

let us introduce a relatively new concept: Agile SCM.

Agile SCM as a concept in its own right was probably

first discussed in detail by Brad Appleton and Stephen

Berczuk in their book Software Configuration Management

Patterns and on the SCM portal CM Crossroads.2

One of their observations was that:

...Configuration Management is going to be

critical "fulcrum" in leveraging a balanced

and effective set of SCM processes and criteria for

agile development methods. With such a large emphasis

on lean and lightweight from the "agilists,"

CM on agile projects will need to be less intrusive/invasive

(what Grady Booch would call low-friction) to

allow agile projects to succeed while at the same time

not being so minimal (due to overreaction) as to contribute

to their failure.

Which concurs with my earlier point that, although

SCM on agile projects tends to be more lightweight and

less visible, SCM itself is a critical requirement of

such projects. It is perhaps no coincidence that the

majority of agile projects adopt entry-level or lightweight

SCM tools such as CVS, Subversion, or BitKeeper -- tools

that have limited but ultimately sufficient functionality

for agile projects. They are also tools that tend to

be less intrusive and value the development experience,

rather than a high-level conformance to a regimented

process.

In theory, however, there is no reason why you can't

use any SCM tool to support agile development practices.

You certainly don't have to use all the features of

a tool, and most tools allow some degree of process

customization, from heavyweight to lightweight and all

places in between. With enterprise tools such as IBM

Rational ClearCase, some organizations are tempted to

use all the "bells and whistles" to define

a heavyweight SCM process simply because the tool can

support it. However, such a process won't necessarily

meet the requirements of your project. To find the right

process and level of customization, you should first

identify and define your requirements, which means understanding

exactly what your development process is, or should

be, and then determining how SCM can support it.

In general, SCM is about "governance" of

the development process; that is, SCM allows projects

to retain a measure of control, but at the same time

allows developers the freedom to create within the process.

With agile development methods, developers typically

have a high degree of freedom and authority to implement

changes. However, one consequence of continuous integration

and test-driven development practices is that they actually

enable a well-disciplined and almost self-governing

approach for SCM. For example, on every code change,

agile developers must first write a unit test, then

write sufficient code just to make the test work, and

then subsequently refactor as necessary to complete

the change. The code change is committed (or checked

in), and its unit tests become part of the integration

suite. Any side-effects of the change are made immediately

visible through the integration build mechanism compiling

and executing the complete unit test suite -- any problems

that are found can be fixed immediately.

In Agile SCM, this governance model is a natural part

of day-to-day development activities and in all consequence

is pretty much transparent to the developers. To understand

this governance model in more detail, let us look at

some different characteristics of SCM and how they would

typically be implemented to support agile development

methods:

- Branches. Agile projects implement simple

branching strategies, typically an Active Development

Line3

and a Release Prep Line. The Active Development Line

is used by developers to commit their changes and

is the means by which continuous integration builds

are carried out. The Release Prep Line is used to

stabilize or engineer a release before making it available

to customers; developers are typically not allowed

to commit changes to it.

- Workspaces. Developers typically have a single

private workspace initially pointing at the collective

set of latest versions of the Active Development Line.

Their workspaces are updated at a minimum when they

start work on a new feature or change request and

just before they commit their changes to the Active

Development Line to check for integration issues.

- Labels. As with traditional SCM, labels are

placed at significant milestones on a collective set

of code versions, at a minimum on every release build,

so that it is possible to reproduce a build environment

if necessary.

- Builds and integration. An automated build

process is a key factor of successful agile development.

The build process typically monitors the Active Development

Line for commits and, if found, automatically executes,

after a grace period, an integration build and unit

test. Notification of the success or failure of this

build is a key communication factor in agile teams.

- Change control. As discussed earlier, there

is an implicit authorization process with agile development

teams; developers are authorized to make changes based

on customer priority or refactoring as necessary.

Requests are recorded either in change control systems,

or even for more informal projects, particularly within

eXtreme Programming projects, on cards or flip charts.

Although SCM characteristics such as these are typical

in agile processes, they are just as likely to be "tuned"

depending on the amount of agility that a particular

project requires. For example, some projects might not

be able to build on each commit but instead initiate

a single daily or nightly integration build. Also, projects

don't exist in isolation; they are normally one of many

projects in an organization. Often, an enterprise organization

contains a mix of both agile and traditional plan-driven

projects, and thus a given project may exist in a particular

market segment. This enterprise context often is the

strongest factor in deciding which SCM toolset is chosen

and which additional aspects of governance the chosen

toolset will need to support.

If you took a single agile project in isolation, its

SCM requirements could almost certainly be met by a

relatively simple toolset. Such a toolset would probably

be used and administered within the project itself.

However, rather than supporting project-specific toolsets,

most large organizations prefer to standardize on a

single SCM toolset and develop organizational processes

around it. There are typically two main reasons for

doing this:

- To reduce the total cost of ownership of the toolset

and its processes

- To be able to conform to a desired (or mandatory)

compliance or regulatory framework

Total cost of ownership is often a subjective issue,

since it includes many quantifiable aspects such as

license, administration, and support costs, as well

as other subjective aspects such as capability or scalability.

Enterprise toolsets such as the IBM Rational toolset

often have higher licensing, administration, and support

costs (certainly initially), but if implemented correctly,

these enterprise toolsets can increase organizational

capability as a whole. They also have proven scalability,

with a single, consolidated infrastructure able to support

large, geographically dispersed development organizations.

As noted above, the main danger of such a toolset is

the temptation to use more functionality than is necessary,

which can strangle agile projects. An organizational

SCM framework will need to be established, and its implementation

should be in some way configurable so as to meet the

needs of different projects.

Recent industry regulations such as Sarbanes Oxley,

Basel II, and CFR 21 Part 11 can place onerous overheads

on SCM processes, particularly with respect to change

control. Although practices such as "segregation

of duties" -- not allowing developers to deploy

to live environments -- should be implemented, the rigorous

enforcement of change control on agile projects can

strangle them. The business cost of not meeting these

regulations is massive, however, so while agile projects

might want to avoid non-essential governance practices,

they have to accept some additional overhead in most

cases. The good news is that if implemented correctly,

an automated SCM toolset can take on most of this governance

aspect, allowing businesses to maintain organizational

control, while allowing individual projects and their

developers to work on the creative aspect of developing

new software functionality to solve business problems.

Let's consider how a balance between governance rigor

and agility can be achieved for agile projects using

the IBM Rational toolset.

There is a common misconception that an enterprise

SCM toolset -- such as the IBM Rational toolset -- cannot

be used to support the implementation of agile development

methods. The significant functionality in these toolsets

is provided to support many different types and sizes

of development environments; consequently, it is not

always easy to identify which elements of this functionality

should be used, and there is a danger that the SCM process

will be over-engineered. Today, there is no out-of-the-box

agile SCM configuration for the IBM Rational SCM toolset.

Instead, it is left to the implementers of the toolset

to find the appropriate configuration to meet their

needs.

The good news is that many organizations have managed

to find such a configuration and are successfully implementing

agile development methods underpinned by the IBM Rational

toolset. From observation, there are a number of best

practices that these projects share. Although these

best practices are not absolute, they should be enough

to give you a framework and starting point for implementing

your own agile SCM process. They can be summarized as

follows:

- Implement a simplified branching strategy.

Agile projects implement simple branching strategies.

In both Base ClearCase and ClearCase UCM (Unified

Change Management), branches ("streams"

in UCM terms) can be created easily and cheaply. There

is therefore often a temptation to define a more complex

branching strategy than is strictly necessary. Agile

projects actively encourage continuous integration

and refactoring, but if developers are isolated on

a branch, problematic or complex merges can occur.

This is particularly true in the case of namespace

refactoring (renaming, adding, or deleting files or

directories). Consequently, most agile projects implement

a specific branch to act as the Active Development

Line and which the developers work on directly. In

Base ClearCase, this is either the main branch or

a specific project integration branch; in UCM, this

is the UCM project's integration stream. To isolate

an environment for a release, a Release-Prep Line

is also typically implemented. This is achieved by

creating a release branch (or UCM stream) off of a

candidate label (or UCM baseline) that has been placed

down on the Active Development Line. This label will

be created either manually -- or more likely automatically

-- as part of an integration build. A diagram illustrating

this structure is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2: To isolate an environment for a release,

a Release-Prep Line is achieved by creating a release

branch (or UCM stream) off of a candidate label (or

UCM baseline) that has been placed down on the Active

Development Line. This label will be created either

manually -- or more likely automatically -- as part

of an integration build.

As well as a simplified branching strategy, agile

projects also tend to configure ClearCase to default

to an "unreserved" checkout model. This

allows developers to check out and check in a file

on the Active Development Line at any point (although

they might be required to do some merging if another

developer has also checked out and in the same file

in the interim). The default ClearCase model is for

the first check out to be "reserved." This

means that you are guaranteed to be able to check

the element back in without having to do a merge.

However, it also means that others can't check out

the element reserved until you put it back and that

people who check out the element unreserved have to

wait for you to check it back in before they can merge.

Such an approach really goes against agile principles.

- Use snapshot-view developer workspaces. If

developers are to work on a single branch, then dynamic

views are not really an option. The power of dynamic

views is that they update themselves automatically

when the branch that they are looking on is updated.

Therefore, if a number of developers have dynamic

views onto a single branch, they will have little

control or isolation in their workspace. Although

developer branches could be implemented, as we have

discussed, this can lead to other issues. Agile projects

therefore typically implement snapshot views, where

the developers are able to update their workspace

to bring in changes from other developers. In practice,

this allows developers enough control and isolation.

- Automate the build process. Single branch

development and incremental check-in can only work

when automated builds and tests are executed frequently.

Most agile projects configure their build process

to execute on every developer check-in. As well as

compiling code, such a build process also validates

new code to see if it conforms to pre-defined coding

conventions and executes unit tests where necessary.

In agile development methods, this practice is often

called continuous integration. Its desired result

is to expose integration problems as early as possible

so that they are easy to address, and also to have

a built, tested, and potentially releasable build

at every stage of the project. Continuous integration

is often intricately linked with the practice of test-driven

development. This is because developers need to implement

unit tests for all aspects of their code to validate

not only that the build has been compiled, but also

that it conforms to some minimum level of functional

quality. In ClearCase terms, the agile project's build

process is set to monitor the integration branch (or

UCM stream) and then execute a build script on check-in.

This is typically carried out by build execution tools

such as CruiseControl (http://cruisecontrol.sourceforge.net)

or IBM Rational BuildForge (http://www-306.ibm.com/software/rational/buildmanagement/).4

- Stage and re-use pre-built binaries. Building

any reasonably complex software application can take

time, from several minutes to several hours. In agile

projects, developers will be delivering and integrating

small changes frequently; they therefore obviously

cannot wait for a two-hour build to complete before

getting feedback. To avoid this situation, agile projects

typically "stage" and re-use pre-built binaries,

and only rebuild the whole system when necessary (for

example, nightly or weekly). There are a number of

ways of staging binaries. ClearCase is often used

to stage binaries, with labels or baselines placed

down on related versions to indicate a composite set

of re-usable binaries. For C/C++ projects, the ClearCase

clearmake utility also has a build-avoidance

mechanism that can be used to automate much of this

staging and re-use process, although there is little

evidence of agile projects using this mechanism. For

Java projects, an alternate approach is to stage pre-built

libraries in a dependency management tool such as

Ivy (http://jayasoft.org/ivy)

or Maven (http://maven.apache.org).

This is particularly appropriate where a project re-uses

a significant amount of open-source components or

where there are issues with transitive dependencies

(i.e., where libraries are dependent on other libraries).

- Release as a composite application. When

it comes to releasing your application, try to release

all your files rather than releasing individual sets.

Most agile projects prefer to deploy the whole or

composite application each time rather than just the

individual files that have changed. Although this

is not a hard and fast rule, releasing the whole application

in the same way each time tends to make the process

more repeatable and prevents problems with missing

files. This practice is more important for agile projects

than more high-ceremony projects, because they produce

an executable, testable, and releasable application

at the end of every iteration. Obviously, this depends

on the target environment for the application. If

it is Web portal, then this approach is fine, but

if it is a consumer application (running on, say,

Microsoft Windows), then a full release cannot be

made to the customer each time a patch is required.

- Limit the use of MultiSite technology. Distributed

agile projects require unrestricted access to a single

codeline. The ClearCase MultiSite technology replicates

complete databases from site to site. To avoid conflicting

changes being made at each site, it implements a concept

called mastership. This means that if a project

is being worked on across multiple sites and developers

are sharing the same branch, then mastership has to

be requested by each developer before they can commit

their changes. There are a number of ways to work

around this issue (including creating site-based integration

branches), but they all add an extra level of complexity

and can slow down the development process. For these

reasons, agile projects tend to avoid MultiSite technology.

This is why the ClearCase Remote Client (CCRC) technology

was developed; it allows distributed development based

off a single server. The first releases of the CCRC

had limited functionality; however, as of the version

7.0 release, it will have sufficient functionality

for the majority of distributed projects. It should

therefore be the recommended way of working for distributed

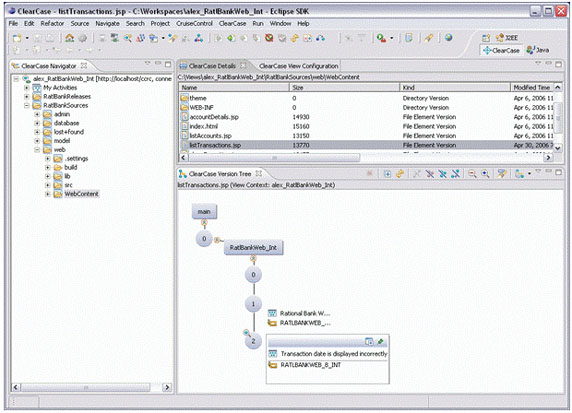

agile projects going forward. The screenshot in Figure

3 illustrates the ClearCase Remote Client working

in an Eclipse environment.

Figure 3: ClearCase Remote Client working in an

Eclipse environment

- Avoid over-customization of ClearQuest change

control. Implement an open or customizable change

request workflow. The IBM Rational ClearQuest tool

can provide a very powerful and sophisticated change-

and defect-tracking facility. Although a number of

agile projects using ClearCase have avoided using

ClearQuest entirely, more and more projects are looking

at ClearQuest and also UCM to see if it can be applied

to help them meet their organization's compliance

and regulatory requirements. Certainly ClearQuest

can have a place in automating the capture, prioritization,

and allocation of a typical change request and feature

backlog, as I mentioned at the beginning of this article.

However, too much process enforcement or micro-management

can make it time-intensive for developers to start

work on new change tasks. If not done with care, this

can significantly slow down the overall development

process and reduce the productivity of the agile project.

To avoid this, agile projects typically implement

a lightweight or customizable ClearQuest change request

workflow. This is particularly relevant where ClearQuest

is being used across an organization. Some projects

in that organization might require more process control

and management, a lot of which can be embedded in

the ClearQuest tool. However, agile projects might

not need or desire the same amount of process control

and management. Organizations working with such environments

have been successful by allowing the change request

workflow to be configurable by each project. However,

such an implementation requires detailed knowledge

of both the ClearQuest tool and the requirements of

different project processes and should not be undertaken

lightly.

In this article, I have discussed the concept of agile

SCM and best practices regarding how it can be implemented

using IBM Rational ClearCase and IBM Rational ClearQuest.

Hopefully, this discussion has convinced you that a

suitable process can be found and implemented to support

agile projects. It is worth noting that the implementation

of an Agile SCM environment is not something that should

be restricted to just agile projects. There are many

projects that do not consider themselves as agile, but

yet have similar SCM requirements. These tend to be

smaller IS/IT projects where the configuration of a

similar environment would be very practical. But it's

worth noting that even larger projects could learn something

by implementing a more lightweight and well-designed

SCM process such as the one described here. In particular,

the practices of build automation (including compilation

and testing), pre-built binary staging, and composite

releasing could be adopted by any project.

There is no reason why an enterprise SCM toolset, such

as the IBM Rational toolset, cannot be used to support

the implementation of agile development methods. The

key is to define and implement an agile SCM process

that focuses on supporting, rather than restricting,

the agile team. It can be a tricky exercise to find

the right governance model for such a team, but a general

recommendation would be to start with a more open

process, only implementing restriction where necessary.

Feedback is also an essential part of agile development

methods. One of the ways that SCM can help with this

feedback mechanism is via an automated build and testing

(and deployment) process. It is therefore recommended

that you invest a significant amount of time looking

at this aspect of your overall process.

1 For a discussion of the relative merits

and successes of agile versus traditional development

methods, see Barry Boehm and Richard Turner's excellent

book, Balancing Agility and Discipline: A Guide

for the Perplexed: Addison Wesley 2004. Alternatively,

for up-to date discussions and case studies on agile

development methods, you can visit and subscribe to

The Agile Journal (http://www.agilejournal.com).

2 Stephen P. Berczuk and Brad Appleton,

Software Configuration Management Patterns. Effective

Teamwork, Practical Integration. Addison Wesley

2003. See also Brad Appleton et al., Streamed Lines:

Branching Patterns for Parallel Software Development.

PLoP Conference: 1998.

http://www.cmcrossroads.com/bradapp/acme/branching/

3 See Appleton, 1998, Op. cit.

4 For more information on how to set up

an automated build environment for agile projects, see

Kevin A. Lee, IBM Rational ClearCase, Ant and CruiseControl.

The Java Developers Guide to Accelerating and Automating

the build process. Addison Wesley 2006.

|